*Seeing Mouchette on big screen on my birthday was one of the best things that could happen. Though my third time watching the movie, it turned out to be a whole new experience in the best possible way. I would like to thank the movie gods and Cinematheque KOFA for this great gift, and will be forever grateful.

“In short, a film that is Christian and sadistic.” -From a trailer made by Jean-Luc Godard for Mouchette

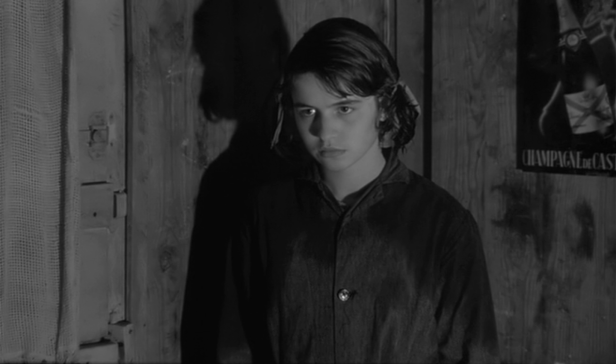

The world inside Mouchette is never short of misery, boredom, meaninglessness, and hatred without a cause; Bresson portrays all this with a sympathetic, yet unsentimental gaze from distance. Arguably the most dramatic event in this film—the rape of a young girl—is another suffering added to Mouchette’s already wretched life. In fact, Bresson shot the scene in the least dramatic and explicit way possible (that is, compared to the overflowing violence and vulgarity that pervade cinema today), only hinting that Arsène is about to rape our little heroine. Though not directly shown, the rape exerts a terrifying presence in the film, as we see how Mouchette reacts to what has happened to her.

For one, there is no one within her reach to whom Mouchette can confide the horror she has gone through. Well, there is one person—her ill mother. By the time she decides to tell her mother about the assault, however, the poor woman passes away. Mouchette is now truly on her own in this mercilessly cruel world. When confronted by a gamekeeper’s wife in regards to the incident, she claims that Arsène is in fact her lover. This scene personally affected me in a very powerful way. I see her denial as defence mechanism of a sort. She has to believe that what’s happened to her is not a rape, but affectionate sex in order to maintain the strength to survive in this world. When Bresson’s camera shows Mouchette’s face during the confrontation, we can see that she is desperately trying to convince herself of the ridiculous lie she has constructed.

But alas, she quickly realises that the lie isn’t enough to get her through the remainder of her misery-stricken life. She stumbles upon a rabbit hunt, and comes face-to-face with her own tragic existence mirrored in the rabbit surrounded by predators and inevitable torments. The only way out for both Mouchette and the quarry is death. Perhaps Mouchette wants to be the one to deliver her own death, before the cruelty of her conditions crushes her. She understands the conditions of her life, accepts the fate as it is, and runs at it with open arms. At the end of the film, we hear a brief splash that seems to indicate Mouchette has taken her own life away.

Some people take this as Mouchette’s redemption, but for me, it is at this point in his career did Bresson’s outlook on human conditions turn to chilling pessimism and the inevitability of broken souls. Mouchette’s death is different from that of Jeanne d’Arc or Balthazar in that it is no martyrdom but an escape. Jeanne d’Arc and Balthazar endure the sufferings exerted on them as long as their physical states allow them to, whereas Mouchette chooses death to put an end to all the sufferings, and it is the only option left to her. “Mouchette offers evidence of misery and cruelty. She is found everywhere: wars, concentration camps, tortures, assassinations,” said Bresson. Not only that redemption is impossible in the world inside Mouchette, but also it does not deserve redemption.

The moments of intense drama and emotion aside, some of the film’s grace also derives from the scenes in which the characters perform seemingly trivial everyday activities: like when Mouchette prepares coffee for her family, or when Louisa pours drinks for the costumers. Knowing how Bresson works with actors whom he called ‘models,’ what we see on screen probably became habitual acts after repeating the same tasks for few dozens times, and devoid of any trace of acting to seem ‘natural.’ Bresson was never interested in staging ‘naturalness,’ but rather in capturing ‘Nature’ itself. Essentially, characters in Bresson’s films are like mechanical mannequins that are programmed to perform precisely what he asks them to. They are blank sheets of paper on which the audience must project their own thoughts and feelings. Bresson’s cinema becomes genuinely immersive because it does not, like most films, simply feed us with emotions, but asks for our visceral investments.

Another immersive element in the film is sound. When we hear something in a Bresson film, we really do hear it—not just as ‘supplement’ to the images, but as an entity with a life of its own. The sound of a cork being removed from a liquor bottle or the sound of worn out clogs being dragged would be inessential noise in most movies. However, in Mouchette (and in most of Bresson’s other films, for that matter), even the most unimportant and undramatic sound sticks out from screen, and gives us an emotional punch. Only a handful of cinéastes regard sound as a major character in a film, and Bresson is certainly one of them. That little splash at the end of the film probably does much more than an explicit image of Mouchette drowned in the lake would.

Bresson always expressed that he would much like the audience to rather feel his film before they think about it. Well, I guess he achieved his goal. I’m unable to form a critical view on Bresson’s films. This may have to with my incompetence as a critic, I don’t know. Even when I determined to view a Bresson film through a critical lens (I tried with Pickpocket and Au hasard Balthazar), I ended up being swept away by a flood of emotions, some of which I did not even know I’d had before. The same happened when I saw Mouchette for the third time, perhaps even more so than before. Say what you will, but I would like to believe that my critical incompetence is, in a way, evidence of his greatness.